city supplements

An alternative urban survey and audio-visual biography of Donegall Street

May 2009 - June 2009

Participating artists: Gemma Anderson; Miriam de Búrca; Keith (Keeth) Winter; Lisa Malone; Kevin Flanagan; Sinéad Bhreathnach-Cashell; Phil Hession.

Location: Different locations at Cathedral Quarter and PS²

Publication: 'city supplements'. A6 format with 7 A3 pull out pages from participating artist +city walks with Robert Scott, Marcus Patton and Declan Hill+ an essay by Bryonie Reid. Published by PS², Belfast 2009,

48 pages, price £5.

ISBN: 978-0-9555358-1-9

Orders via bookshops or pssquared

Walking tours - starting at PS²

-future city- Keith Winter: Friday 5 June 6pm

-playground city (for children 4-10years): Lisa Malone/ Sinéad Bhreathnach-Cashell: 25 May,

12am

Opening hours: Mon-Sat 1-6pm, Sun 10am-4pm

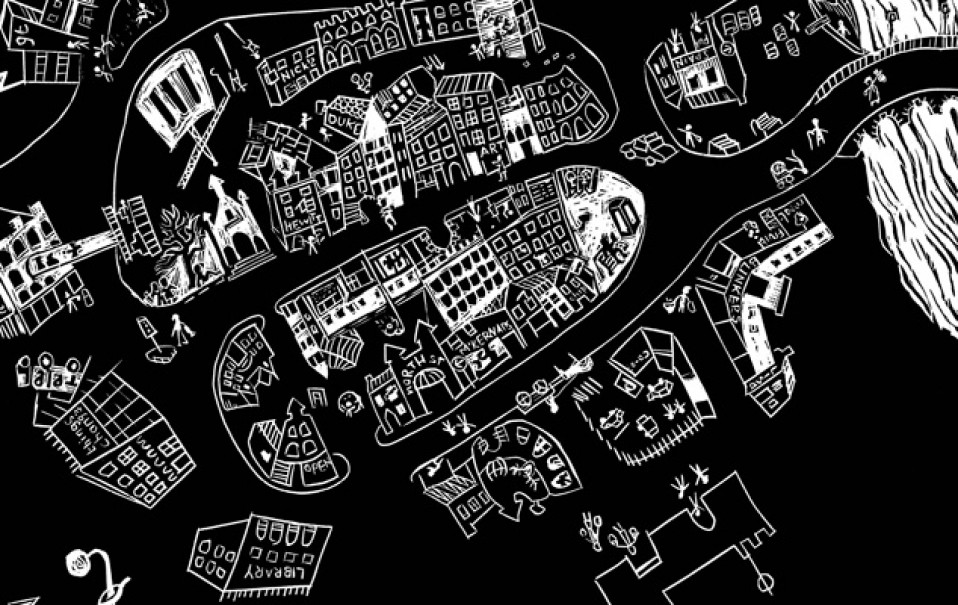

For city supplements, PS² invited seven artists to be home-tourists in Belfast and go on a walk around the Cathedral Quarter, where PS² is based. Walks without a map and without the usual ‘sites of interest’ in mind, equipped instead with curiosity and a compass of imagination.

The visual responses of this alternative urban survey are as diverse as the work practice of the artists; from video film and photogramm to futuristic animation and playful collage.

These subjective supplements recover local information and interpretations of hidden natures, darkened outlooks and green alternatives.

They are socially and ecologically oriented proposals to a master plan of the inner city

Images and signs of these alternative maps are placed at different locations around Cathedral Quarter and should invite for a personal walk and discovery.

Gemma Anderson, photogramm

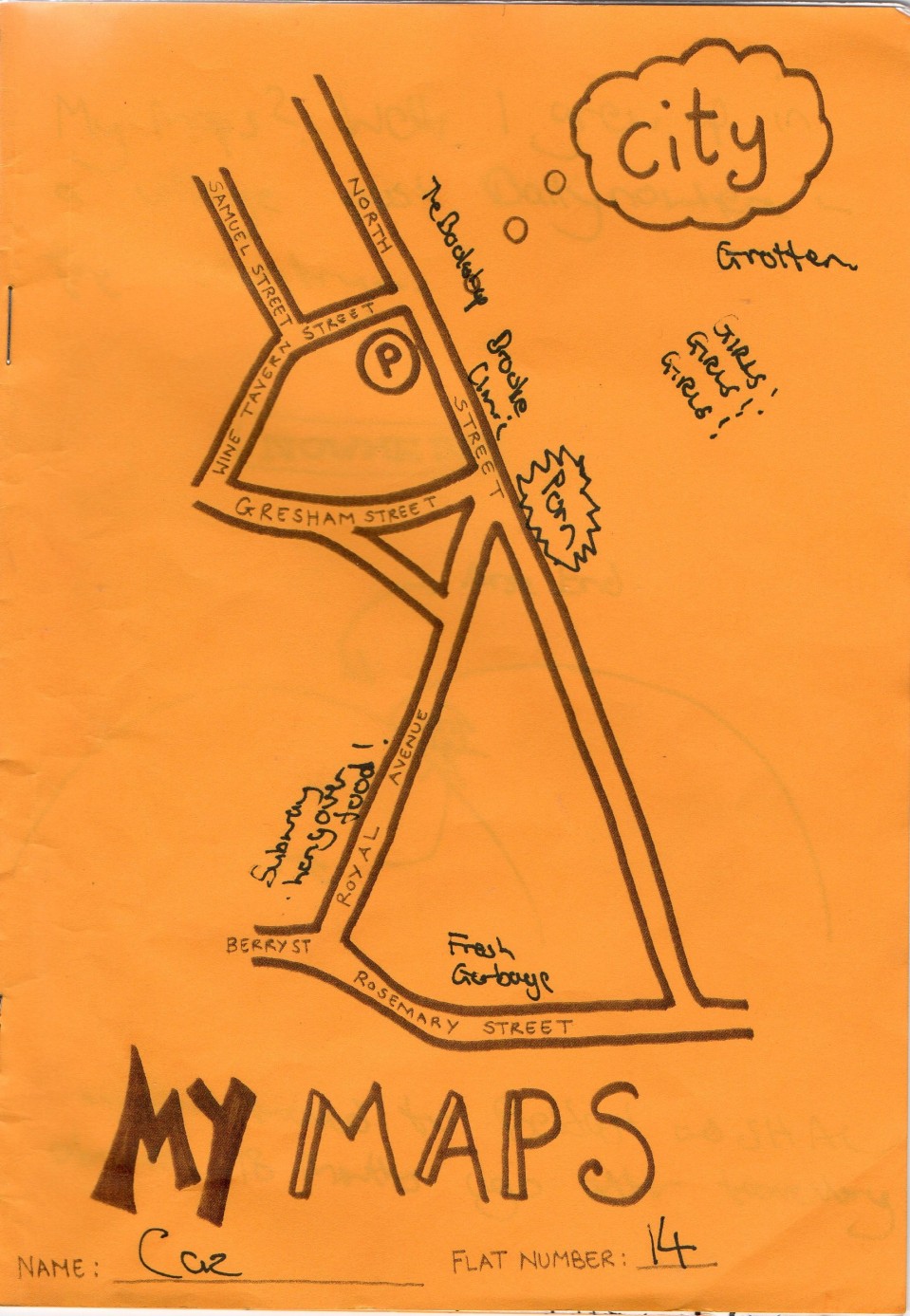

Sinéad Bhreathnach-Cashell: map making course- unknown participant

Introduction

Supplement

1] an addition designed to make something more adequate

2] a magazine distributed free with a newspaper.

3] a section added to a

publication to supply further information or correct error

4] (of money) an

additional payment to obtain special services

5] to provide an addition to

(something), esp. in order to make up for an inadequacy…’

Source: Collins Compact English Dictionary, Harper Collins, Glasgow, 1998.

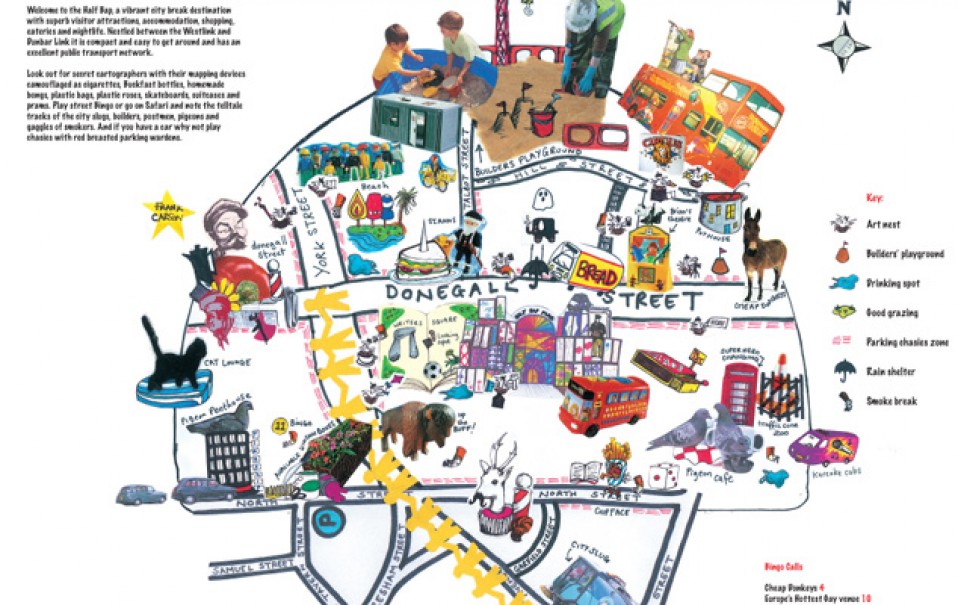

If one visits a bigger city, one buys a map - for orientation and tourist information, with street index, places of interest, notable buildings, museums, parks, bus routes and more. The map from the Tourist Office in Belfast also contains three different trails; a Christian Heritage - , a Titanic - and an Art Trail, (which features on the legend in second position, after the bed sign for hotels). Pretty good for the arts and for tourists in the city, the five grid distance between The Ulster Museum and - say PS² - mean a walk of 25 minutes. However PS² is not on this map, showing how maps and map makers are selective. What gets noted down, measured and indicated depends

which purpose it serves. The Ordnance Survey Map, on which most maps are based, reveals in its name (and arrow in its logo), the military origins of control and order, dominance and colonisation. The scribbled

directions to the best second hand shop on the back of a receipt represents the other, unofficial end of cartography. Drawings of directions, shortcuts or the way to hidden places are produced ‘to supply further information or to correct an error’, as the definition of supplements states. A map created from personal knowledge of a place,

an insider addition, a city supplement.

Which is what this project and the guide in particular tried to do: to ask some people about their knowledge and understanding of a small area in Belfast. Not just any part, but one of the oldest of the city, Cathedral

Quarter, where PS² is based. We asked experts about special subjects and went on a walk with them:

how the built environment changed in Donegall Street over the centuries, which birds nest on roof tops in Lower Garfield Street or how North Street might look in the near future. Walks within one grid- a 5

minute distance- and lots to see and learn in between.

And we asked non-experts, seven artists, mostly young and mostly not from Belfast, but all currently living and working here.We asked them to be home-tourists, without a map, without the ordnance surveyed

‘sites of interest’, equipped instead with curiosity and their individual compass of imagination. Their brief was, to walk around and explore the environment, without fixed directions and clear destination. Free of

any purpose, like a poem or child’s play. Except, we wanted their map of the area, their scribbles or image of whatever they found important on their alternative urban survey. The visual responses were as diverse

as the work practice of the artists; from video films and photographs to notebooks and a miniature area model in a suitcase. These subjective supplements recover local information and interpretations of hidden natures, of green alternatives and darkened outlooks. Aspects of the inner city, between proud and troubled pasts, re-generated or imposed futures. The supplement maps mark the ecological potentials of car parking sites and pools of human interaction in shops. They note the preying bird in the Google map survey over St.Anne’s Cathedral and

the rough sleepers on a park bench. What they have in common is a potential for change and an engagement

in the environment, green or futuristic, social or alternative. The supplements can be seen as proposals, as small and often beautiful additions to a master plan for the Cathedral Quarter. Any of us could

make further additions, make our own city supplement. All it needs is curiosity and time for a leisurely walk through the city. One will soon start to discover, appreciate, dislike and wishfully imagine aspects of

the urban environment. From there, it is only a few steps further to be engaged, to act, to lobby.

Perhaps ‘city supplements’ will be a useful guide for your own city walk.

Cathedral Quarter

Keith Winter: Critical Humdrum

Untold stories, unseen spaces: city supplements [1]

Introduction: Bryonie Reid

city supplements constitutes an alternative map of the Cathedral Quarter, and my objective here is to consider certain productive possibilities inherent in the project. The artist-mapmakers explored the area with an eye to its marginal and vernacular histories and the nuances of its topography, with an underlying commitment to observing, understanding and helping to shape place sustainably and sensitively. I

view this practice as a form of psychogeography. Originating in Situationist art of the mid-twentieth century, psychogeography is defined by Iain Borden as ‘a kind of alert, constructive and transgressive “drift” across city spaces’ which aims to uncover ‘the accidental and hidden facets of urban life’.[2]

In Belfast, a thoughtful psychogeography

can attend to the real complexity of the urban landscape and its inhabitants across time, in disruptive contrast to simplistic and sectarian notions of terrain as either Protestant or Catholic, unionist or nationalist. Further, psychogeography can be an ethical exercise for people living and working in a city whose fraught history and

fragmented geography are being papered over by rapid regeneration. Bound up in this project and in psychogeographical rituals are the ideas of locality, walking and memory. I address these in the remainder of the essay, suggesting that each offers the potential for creative and responsible rethinking of spaces blighted by exclusion and violence, and whose hasty renovation risks the loss of their rich and problematic pasts.

locality

Historian Brian Turner points out that ‘one of the first things any study of locality shows is that things are not as simple as they seem’. [3]

Other cultural commentators have suggested that in Northern Ireland, local studies may help to ‘subvert …centralising narratives’ which at their worst suggest a timeless and zero-sum struggle for identity and territory between a monolithic Britishness and a monolithic Irishness. [4] In fact, Catherine Nash shows that although Northern Ireland is represented as overburdened with history, there is in fact ‘too little – little apart from

the opposing Nationalist and Unionist narratives, and little as a result of the neglect of the history of Northern Ireland in schools’. [5] Elsewhere Turner proposes that studying localities has an ethical dimension, noting ‘the increasing gracelessness with which we treat our surroundings’. He believes that attention to local landscapes moves

them from the realm of ‘blanknesses to be crossed in getting to somewhere else’, or in Belfast’s case, redeveloped, into that of intricately textured spaces significant for both collective and individual identities. [6]

LIsa Malone: map, lino cut

Phil Hession: The Black Marlin

Lucy Lippard contends that artists can aid this process, advocating a ‘place-specific art’ which ‘become[s] at least temporarily a part of, or a criticism of, the built and/or daily environment, making places mean more to those who live or spend time there’. [7] In a city where territory is key, examining specific streets with an open-minded curiosity should produce an account of place which acknowledges painful and politicise histories but also reveals the myriad other human interactions which

combine to give those streets the texture and meaning identified by Turner and Lippard.While urban landscapes are inherently fluid, change is not always positive, nor progressive, and especially not when economic imperatives override all other considerations. The practice of observing, researching and mapping a small urban locality uncovers unfamiliar stories and pieces together a picture of its evolution through time. It can be read as a positive contribution to the important process of developing subtle and nuanced senses of place which make room for more than one identity and demand responsible redevelopment.

walking

One means of becoming intimately acquainted with locality is to move through it on foot, and of course, the micro-scale of the local facilitates its exploration by walking. David Pinder believes that walking offers situated, fluid and embodied perspective on place, particularly suited to the study of urban streets and the production of alternative

cartographies. [8] It could be argued that a walked map is a form of ethics; it foregrounds the subjective, physical and mutually constitutive relationship of the cartographer with the landscape in place of the putatively objective, all-seeing and indifferent eye of technology. Tim Robinson explains that producing his map of Connemara ‘took…a total of several years of walking to cover the ground, and some of this was a wearisome struggle against wind and rain and cold’, but that in this

way ‘I got the feeling of the place, its obdurate reality, into my bones’, with a resultant effect on the document he produced. In light of landscape’s constant but gradual transitions, ‘the map itself could hardly then be more than an interim report on the progress of its own making’. [9]

The walking described above is an ideal type, involving bodies secure in their right and ability to cross landscapes safely on foot, and Pinder acknowledges that ease of exploration ‘is bound up with axes of power’ which in the Western world usually favour white middle-class men. [10] Rebecca Solnit highlights the gendered nature of walking, pointing out that ‘the English language is rife with words and phrases that sexualise women’s walking’. This limits their uses of, and comfort in, urban space

in a way that persists to an occasionally shocking degree. [11]

Sinéad Bhreathnach-Cashell- map

Bryonie Reid- public plaques

Belfast is typical of most other cities in this sense, but the meanings of its so called public space are heightened and complicated by sectarian as well as gender and class politics. Securing territorial identity is crucial to political struggle, and Belfast’s fractured sectarian geography arises from the fear of attracting violence by being discovered in the wrong place.

A self-reinforcing process of psychological and physical limitation persists today. In times of relative peace, compromised though these have been recently, the act of walking Belfast’s streets is an important contribution to opening out its geography.

Lisa Malone: Belfast 16th -21st century

memory

Pierre Nora considers memory (lived, mutable and informal) to ‘fasten upon sites’, while history (documented, fixed and official) ‘fastens upon events’, suggesting that discussion of memory is particularly apposite here in relation to locality and walking. [12]

Michael Hebbert proposes that perhaps ‘only spatial imagery has the stability to allow us to discover the past in the present’, and therefore to construct our sense of ourselves, but urban space is especially unstable. [13] Solnit views

accelerated change in this arena critically, contending that it is then that ‘a disjuncture between memory and actuality arises, and …one becomes… an exile at home’. [14]

Accused of an excessive sense of history, Northern Ireland is characterised too as overindulging in remembrance. Edna Longley argues that here, remembering ‘works symbiotically to repress and exclude’, with ‘cynical, selective forgetting’ taking the place of ‘responsible, alarming memory’. [15] Remembering is a process fraught with emotional and political overtones in any context, but in Belfast, it is cross-cut again by sectarian tensions and conflicts. Belfast’s redevelopment, markedly evident in the Cathedral Quarter, is described and justified in economic terms and has helped to revitalise a social and commercial infrastructure degraded or destroyed by years of conflict. However, the economic imperative to build anew risks aiding the political imperative to forget by erasing the topography of memory, always problematic in societies with a history of conflict. This topography points to a vast and constantly evolving body of individual and collective experiences, private and public, and includes ordinary as well as bloody and traumatic events. Focusing on an area undergoing redevelopment, careful and even handed remembering is a significant practice. The city supplements project acts to fill in the gaps in our spatial and historical knowledge of the Cathedral Quarter, encouraging others to seek out fresh perspectives on spaces they are familiar with to varying degrees.

Miriam de Búrca: Azalea

conclusion

Rosalyn Deutsche states that ‘as a practice within the built environment, public art participates in the production of meanings, uses and forms for the city’. [16] It has been suggested that public art in the Cathedral Quarter can shore up its representation as an apolitical space of economic regeneration, neutral in terms of Irish and Northern Irish

history, [17] or it can brush against the grain [18] of this surface perception to reveal its snags, complexities and contradictions. city supplements, I think, is a work of the latter type. I have characterised it as a kind of psychogeography and identified three of its conceptual and practical components as locality, walking and memory. I have proposed that working with each of these offers the possibility of meaningful intervention in the urban landscape, and for particular reasons in Belfast. In a city where attempts have been made to fix spatial histories and identities, city supplements acts as a reminder that being an ‘exile at home’ need not be simply an experience of alienation. Rather, the opportunity to see everyday spaces in novel and sometimes strange ways, is also an opportunity to sidestep sectarian and even economic certainties. Viewed alongside other efforts to open up Belfast’s streets to tourists from Northern Ireland and elsewhere, city supplements participates modestly but significantly in the process of re-imagining the city.

1] Paraphrased from Rebecca Solnit, ‘The Art of Memory and the Art of Forgetting’, pp31-48 in Liam Kelly and Mary McDonagh (eds.) Placing Art: a Colloquium on Public Art in Rural, Coastal and Small Urban Environments, Sligo, Sligo County Council and Sligo Borough Council, 2002, p32.

2] Iain Borden, ‘The City of Psychogeography’, pp103-104 in Architectural Design, vol.69 no.11, 1999, p104 and p103.

3] Brian Turner, ‘A Sense of Place’, p30 in Fortnight, no.279, 1989.

4] Peter Carr, ‘A “MistressWithout Masters”: Lyotard, Foucault and Local History’, pp75-80 in Ulster Folklife, no.43, 1997, p77.

5] Catherine Nash, ‘Local Histories in Northern Ireland’, pp45-68 in History Workshop Journal, no.60, 2000, p50.

6] Brian Turner, ‘Introduction’, pp5-7 in Brian Turner (ed.) The Heart’s Townland: Marking Boundaries in Ulster, Downpatrick, Ulster Local History Trust in association with Cavan- Monaghan Rural Development Co-operative Society, 2004, p5.

7] Lucy Lippard, The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society, NewYork, New Press, 1997, p263.

8] David Pinder, ‘Arts of urban exploration’, pp383-411 in Cultural Geographies, vol.12 no.4, 2005, p402.

9] Tim Robinson, Setting Foot on the Shores of Connemara and OtherWritings, Dublin, Lilliput Press, 1996, pp79 and 76.

10] Pinder, Arts of urban exploration, p402.

11] Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: a History of Walking, New York, Viking, 2000, p234.

Significantly, the term ‘streetwalker’, when applied to a woman, means prostitute. When Solnit complained to friends of frequent and sometimes violently expressed sexual harassment when she walked her San Francisco neighbourhood at night, she was advised to ‘stay indoors at night, to wear baggy clothes, to cover or cut my hair, to try to look like a man…to take taxis, to buy a car…to get a man to escort me’, all of which suggested that she should not expect either to walk freely as a woman, or to walk at all (p241).

12] Pierre Nora, Realms of Memory: the Construction of the French Past, New York and Chichester, Columbia University Press, 1996, p18.

13] Michael Hebbert, ‘The street as a locus of collective memory’, pp581-596 in Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol.23 no.4, 2005, p584.

14] Solnit, The Art of Memory, p44.

15] Edna Longley, ‘Northern Ireland: Commemoration, Elegy, Forgetting’, pp223-253 in Ian McBride (ed.) History and Memory in Modern Ireland, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp228 and 253.

16] Rosalyn Deutsche, Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics, London and Cambridge

(Massachusetts), MIT Press, 1996, p56.

17] John McCarthy, ‘Regeneration of Cultural Quarters: Public Art for Place Image or Place Identity?’, pp243-262 in Journal of Urban Design, vol.11 no.2, 2006. See also Daniel Jewesbury, ‘Blurred vision’, pp18-20 in Circa, no.93, 2000, and Declan Long, ‘Selective memories, collective histories’, pp50-58 in Circa, no.123, 2008, for discussions and critiques of public art in Northern Ireland.

18} Paraphrased from Walter Benjamin, quoted in Deutsche, Evictions, p79.

Keith Flanagan: Line of Flight

Demarcation

http://keefwinter.com/Keith Winter: FUTURE TOUR - Friday 5 June, 6pm

Keith Winter: FUTURE TOUR - Friday 5 June, 6pm

Miriam de Búrca: Azalea

'city supplements' was funded by Awards for All, National Lottery